Using Zod to Parse Function Schemas

March 11, 2022 - 5 min readData validation, ensuring the data your system receives is in some expected shape, is crucial for a mature system. The most important part of a system, the business logic, expects and provides data in a particular shape, and so validating these shapes is an important part of running and testing your business logic.

There are a ton of options. TypeScript is widely used and will provide compile time checks on your code. Most systems require runtime validation at its boundaries. For example, I may have a web server endpoint that expects a certain payload shape that it will need to validate, at runtime. I can’t use TypeScript for that. In addition, TypeScript adds a build step (unless you use Deno 🙂), and TypeScript checking can be bypassed using catchall types like any and unknown. I can disallow those types, using strict, but I now am beholden to library types, types I don’t have control over or may be incorrect. So then using the any escape-hatch becomes an exercise in design and discipline, for each dev that works on the system. At the very least, that’s cognitive overhead that can’t be ignored, and at its worst, an obstacle to delivering quality software.

My last points were not to knock TypeScript, it’s great and we use it. My point is that it takes experience and discernment to know where TypeScript is a boon, and where TypeScript is an obstacle. TypeScript catches tons of common bugs, but it’s just another tool in the toolbox. It takes a good developer to decide how and when, and to what extent, to use it.

So regardless of using compile time checks, we need some way to validate data shape at runtime, so that bad data doesn’t get into the crucial parts of the system. There are tons of runtime options. Joi or Yup are both great runtime options. At hyper, we use a library called Zod.

At hyper

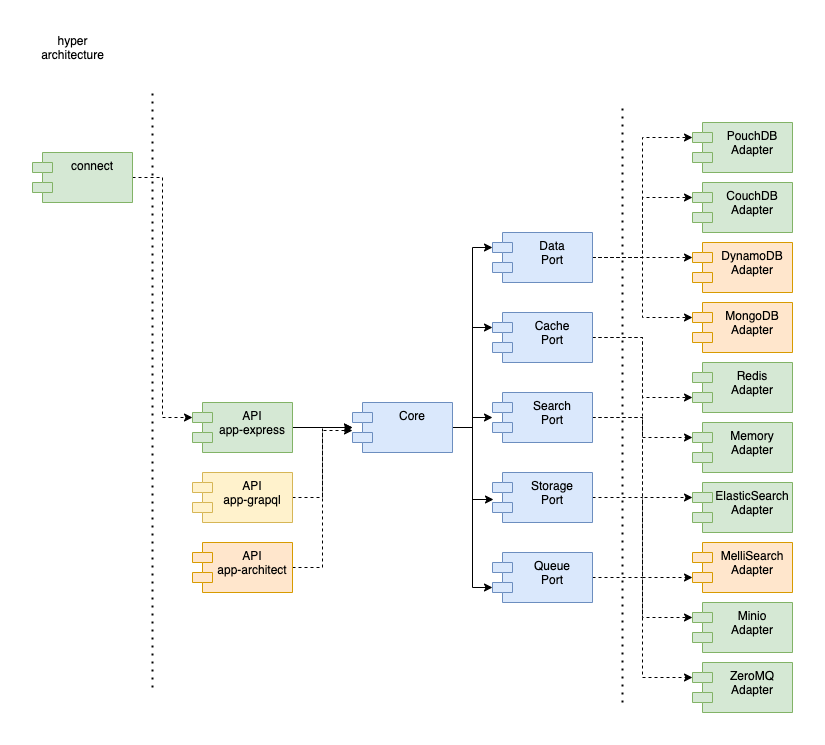

The hyper service framework we’ve built at hyper, uses a “Ports and Adapters” architecture, also known as Hexagonal Architecture. This allows swapping out the underlying components that power hyper services, without having to change the hyper core.

To accomplish this architecture, hyper core must specify a contract or “port”, for each service that it offers. Then a service adapter must implement one of those ports in order to be used by hyper core:

Each of these ports are published modules. You can see hyper’s data port here. All service ports are implemented using zod. We define a Zod schema for the adapter object. Then, given an adapter implementation, the port wraps each function implemented by the adapter with the corresponding z.function() schema that enforces the contract between hyper core and the hyper adapter. Zod even has a feature that allows TypeScript type inference from schemas!

function schemas are a really cool feature of zod as they allow for separating the validation logic from the “meat” of the implementation. Adapters don’t have to worry about validating inputs and outputs for each function implemented; hyper core does that. In fact, as an adapter developer, you can use the hyper port as part of your unit tests, ensuring your adapter returns the proper responses for each api!

import { data } from 'https://x.nest.land/hyper-port-data@1.2.0/mod.js'

// wrap your impl with the port

const myDataAdapter = data({...})

/**

* Now simply assert each api call,

* and Zod parses the inputs and outputs.

* If the test doesn't throw,

* you know you've implemented the port!

*/

test('should return the correct shapes', async () => {

assert(await myDataAdapter.createDatabase('foo'))

...

})This is precisely how hyper core wraps each adapter.

A function schema

A function schema in zod looks like this:

const MyFunctionSchema = z.function()

.args(

z.string()

)

.returns(

z.promise(z.object({ ok: z.boolean() }))

)You can then pass a function to the schema’s implement method, which returns a new function that automatically validates its inputs and outputs:

function businessLogic (str) {

... // do some stuff

return Promise.resolve({ ok: true })

}

const withValidation = MyFunctionSchema

.implement(businessLogic)

withValidation('foo') // passes

withValidation(123) // throws ZodError because input doesn't match schema

MyFunctionSchema.implement(

str => Promise.resolve({ not_ok: true })

)('foo') // throws ZodError because output doesn't match schemaFunction overloading

You may have a function that supports multiple input shapes and multiple output shapes. Zod does have support for Union types which works as a sort of logical OR type, And you could use those to build a function schema:

const stringOrNumber = z.union(

[z.string(), z.number()]

)

const identity = z.function()

.args(stringOrNumber)

.returns(stringOrNumber)

.implement(i => i)

// equivalent TS type

type stringOrNumberIdentity =

(i: string | number) => string | numberThis works if either input can produce either output, but if there is a 1:1 relationship between input and output, then we will need something different. For that, what we really want is a type like this:

type stringOrNumberIdentity =

(str: string) => string | (n: number) => numberWe can accomplish this with two zod function schemas, and then parsing the argument using each schema’s parameters() api. parameters() returns the Zod schema for the input args:

const strIdentity = z.function()

.args(z.string())

.returns(z.string())

// schema for the args of strIdentity

const strInput = strIdentity.parameters()

const numIdentity = z.function()

.args(z.number())

.returns(z.number())

const myFn = ....

const identityWithValidation = z.function()

.args(stringOrNumber)

.returns(stringOrNumber)

.implement(i => {

if (strInput.safeParse(i).success)

// parse i/o as string

return strIdentity.implement(myFn)(i)

// parse i/o as number

return numIdentity.implement(myFn)(i)

})With this, we can enforce a 1:1 relationship between input and output, for an overloaded function.

Conclusion

A system will need some sort of runtime validation eventually. Consider separating your validation logic into composable pieces using a library like zod